| 최초 작성일 : 2025-09-17 | 수정일 : 2025-09-17 | 조회수 : 27 |

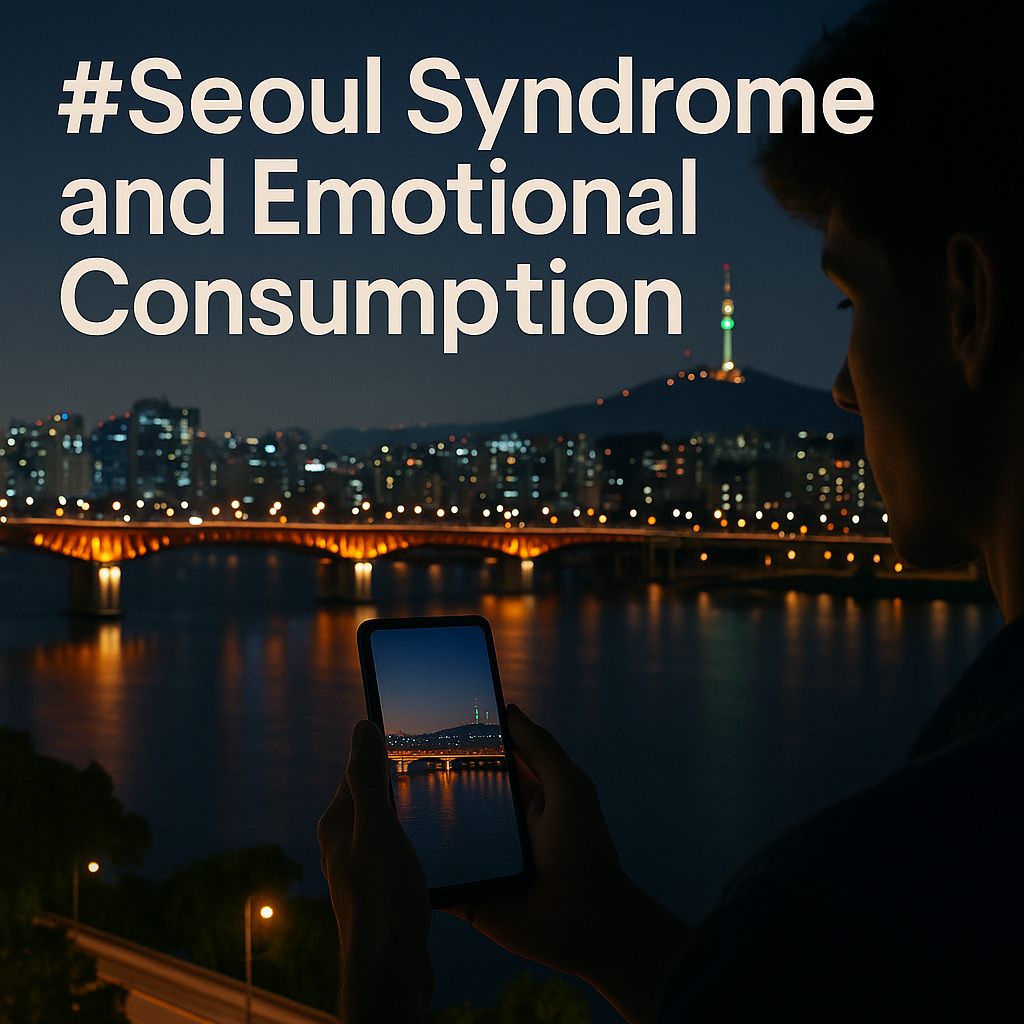

“Seoul Syndrome” has emerged as one of the most striking cultural phenomena of the mid-2020s, capturing headlines across Asia and beyond. The term describes the emotional longing of global youth—particularly in China, but also in Southeast Asia, Europe, and North America—for Seoul as more than a city. It represents an imagined lifestyle, an aspirational identity, and a cultural symbol. On platforms such as Weibo, Xiaohongshu, and TikTok, thousands of posts proclaim “I miss the Han River” or “I want to walk in Hongdae’s streets” even from those who have never visited South Korea. This is not simply wanderlust. It is a reflection of how Seoul has become an emotional commodity in the global imagination. Unlike traditional tourism marketing that emphasizes attractions or shopping, Seoul’s global appeal is deeply tied to its symbolic meaning. Young people see Seoul as a stage of identity construction. Watching K-dramas, listening to BTS or NewJeans, reading webtoons, or scrolling through Korean lifestyle influencers, they are not just consuming media; they are participating in a narrative of modern cosmopolitan life. Seoul’s neon-lit Gangnam streets, tranquil Han River parks, or indie cafés in Itaewon are all cultural scripts waiting to be enacted. Academic theories help us decode this phenomenon. Pine and Gilmore’s Experience Economy explains why youth seek experiences rather than material possessions, and Seoul offers exactly that: a sense of belonging in a globally recognized culture. Bowlby’s Attachment Theory shows how people can form strong emotional ties to spaces—even imagined ones—through mediated exposure. Bourdieu’s Cultural Capital highlights how referencing Seoul culture signals sophistication and cosmopolitanism among peers. And Appadurai’s mediascapes reveal how global media flows continuously reproduce Seoul’s image, making it feel familiar even to those thousands of miles away. Empirical data backs this trend. According to the Korea Tourism Organization, Seoul welcomed over 13 million foreign visitors in 2024, a 22% increase from pre-pandemic levels. On TikTok, hashtags like #Seoul and #HanRiver have amassed billions of views, indicating how the city circulates as a cultural brand far more widely than actual visits suggest. Reports by South China Morning Post and Nikkei Asia confirm that young Chinese travelers list Seoul as their top dream destination, ranking above Tokyo, Paris, and New York. This shift illustrates how emotional branding can outweigh traditional prestige in global city competition. The implications are vast. Economically, Seoul Syndrome fuels growth in tourism, retail, beauty, and F&B industries. Socially, it highlights how cities function as identity anchors for global youth seeking meaning and belonging. Politically, it elevates Korea’s soft power, positioning Seoul as a cultural capital of the digital era. Yet there are risks. As Seoul becomes hyper-commodified, local residents face housing crises, overcrowding, and cultural gentrification. Without careful planning, the very identity that attracts global youth may erode under the pressures of mass consumption. Ultimately, Seoul Syndrome is not about a single city but about a new way global youth consume identity through space. Seoul has become a mirror for aspirations, anxieties, and dreams of a generation navigating rapid globalization. Its rise shows that in the 21st century, cities no longer compete only with GDP or skyscrapers—they compete for emotional resonance. And right now, Seoul is winning that competition.

Chosun Ilbo (2025.09.15) – “Chinese MZ Generation Says, ‘I Miss the Han River’ – Seoul Syndrome Spreads Online” BBC Culture (2024.11.10) – “Why Global Youth Are Consuming Cities as Lifestyle Brands” The New York Times (2025.01.03) – “K-pop and the Global Seoul Effect” South China Morning Post (2025.02.14) – “Seoul as a Dream Destination for Young Chinese Travelers” The Guardian (2024.12.21) – “Emotional Consumption: From Luxury Goods to Cityscapes” Nikkei Asia (2025.03.19) – “Korean Soft Power and the Rise of Seoul as a Global Cultural Hub” -------------------------------------- In September 2025, Chosun Ilbo reported that Chinese MZ youth increasingly post nostalgic comments about Seoul on Weibo and Xiaohongshu—statements like “I miss the Han River” or “I long to walk the streets of Hongdae.” These are not expressions from people who once lived in Korea but from those who have never been there. This paradox—feeling homesick for a place never visited—signals a profound cultural shift. Meanwhile, BBC Culture highlighted a broader global trend: cities are consumed like lifestyle brands, where images of Tokyo, New York, or Paris circulate as cultural products. Yet Seoul stands out as particularly resonant in 2025. The New York Times emphasized the “Seoul Effect” fueled by K-pop, dramas, and digital media. South China Morning Post noted that young Chinese travelers rank Seoul above Paris and Tokyo as their dream destination. And The Guardian connected this to the broader rise of emotional consumption, where people purchase not just products but identities. Taken together, these reports reveal an important shift. Cities are no longer consumed only by residents or tourists who physically inhabit them. They are also digitally consumed and emotionally inhabited through stories, images, and cultural flows. Seoul has become a symbolic landscape that global youth imagine themselves part of—even from thousands of miles away. This raises pressing questions for both scholars and policymakers: Why Seoul, and why now? Why does Seoul resonate more deeply than other global cities? And how should Korea respond to this surge of attention, balancing global branding with local realities?

To understand why “Seoul Syndrome” resonates so strongly with global youth, several academic frameworks are useful. These theories do not directly explain Seoul itself but provide conceptual tools to interpret the broader shift in how cities are consumed in the 21st century. Experience Economy (Pine & Gilmore, 1999): This framework argues that the most valuable economic offering today is no longer goods or services but memorable experiences. Seoul functions as such an experience—walking by the Han River, visiting a K-drama filming location, or sharing a TikTok video of Hongdae nightlife becomes part of one’s identity narrative. Attachment Theory (Bowlby, 1969): Traditionally applied to human relationships, this theory has been extended to place attachment. It explains how individuals can form deep emotional bonds with spaces—even imagined or mediated ones. Through media exposure, Seoul becomes a symbolic attachment object for those who have never set foot in Korea. Cultural Capital (Bourdieu, 1984): Knowledge of Seoul’s culture, from K-pop fandom to Korean beauty products, functions as symbolic capital. Referencing Seoul or displaying familiarity with its trends signals cosmopolitan identity and social distinction among peers. Mediascapes (Appadurai, 1996): Appadurai’s concept highlights how images and narratives circulate globally, producing imagined worlds. Seoul’s media saturation across YouTube, Netflix, Weibo, and Instagram turns it into a globally accessible cultural symbol, reproduced endlessly in the digital sphere. Place Identity Theory (Proshansky, 1978): This theory emphasizes how urban environments contribute to self-identity. For global youth, Seoul operates as part of their psychological map. To “be into Seoul” is to signal openness, modernity, and emotional sophistication. Dramaturgical Theory (Erving Goffman, 1959): Goffman’s idea of life as a performance suggests that cities can be stages for identity construction. Seoul, with its iconic backdrops and cultural scripts, offers ready-made scenes for global youth to perform modern, stylish selves online. Simulacra and Hyperreality (Jean Baudrillard, 1981): Baudrillard argued that in a media-saturated world, images become more real than reality itself. Seoul exemplifies this: many experience it more through Netflix dramas and TikTok edits than through physical travel, consuming the idea of Seoul rather than the place. Together, these frameworks provide a powerful lens: Seoul Syndrome is not simply about tourism or pop culture. It reflects how cities today function as emotional, symbolic, and digital commodities—consumed globally as part of personal identity formation.

When viewed through the combined theoretical lenses, “Seoul Syndrome” is best understood as the emotional commodification of an entire city. Conventional news reports often describe it as a surge in tourism demand or a spike in K-pop’s global popularity. Yet this theoretical analysis uncovers deeper forces at play—why Seoul, more than other global cities, has become such a powerful symbol for global youth. First, Seoul embodies hybrid modernity. Unlike New York, which symbolizes financial power, or Paris, which conveys romance, Seoul communicates a different narrative: technologically advanced, yet intimately relatable. A late-night visit to a convenience store, a picnic along the Han River, or strolling in Hongdae after dark are not extraordinary luxuries. They are everyday moments imbued with emotional significance. Global youth are drawn to Seoul precisely because it presents a lifestyle that feels both aspirational and achievable. Second, Seoul is consumed digitally and daily. Millions of people interact with Seoul content without ever boarding a plane. TikTok videos tagged #Seoul or #HanRiver generate billions of views. On Weibo and Xiaohongshu, hashtags like “living in Seoul” trend regularly. YouTube vloggers tour Seoul neighborhoods for international audiences, and Netflix dramas export images of Seoul apartments, cafés, and streets worldwide. Through these platforms, Seoul is transformed into an imagined experience accessible from any smartphone. Third, Seoul has become a form of cultural capital. To reference Seoul in conversation, fashion, or social media posts signals cosmopolitan belonging. Knowing the difference between Gangnam and Hongdae, following Korean skincare routines, or attending K-pop concerts abroad functions as a badge of sophistication. For many young people, being “into Seoul” is not just fandom; it is a way of performing global modernity. Fourth, Seoul Syndrome reflects the rise of emotional consumption in urban branding. Cities are no longer competing solely for financial investment or infrastructural prestige. They are competing for emotional resonance. Seoul’s ability to evoke nostalgia even in those who have never visited demonstrates how far this competition has progressed. The Han River has become less a physical location and more a digital symbol of belonging and aspiration. Finally, Seoul highlights the risks of over-commodification. As the city becomes hyper-branded, residents face rising housing costs, over-tourism, and cultural homogenization. The Seoul that global youth imagine may diverge sharply from the lived experiences of citizens dealing with inequality and urban stress. This tension between global desire and local reality poses one of the greatest challenges for sustainable city branding. Taken together, these dynamics illustrate why Seoul Syndrome matters. It is not only about the global spread of Korean culture but also about how global youth construct their identities through cities. Seoul serves as both a canvas for personal imagination and a stage for digital performance. Unlike other cities, it offers a combination of relatability, accessibility, and symbolic richness that resonates with a generation seeking meaning in a fragmented world. In this sense, Seoul Syndrome is less about Korea alone and more about the future of cities everywhere. As globalization accelerates, cities are increasingly judged not just by their economic strength but by their emotional appeal. Seoul, for now, stands at the forefront of this shift—an urban brand that captures both the heart and the imagination of global youth.

The phenomenon of “Seoul Syndrome” carries several implications. For policymakers, it highlights the urgent need to balance global branding and local sustainability. Seoul’s rising emotional value attracts visitors and investors, but without careful planning, it could also intensify housing pressures, gentrification, and social inequality. Policies should therefore promote sustainable tourism, protect cultural diversity, and ensure that local residents benefit from the city’s rising brand equity. For businesses, Seoul Syndrome offers a blueprint for the future of experience-based markets. Companies in fashion, food, entertainment, and tech can leverage the city’s symbolic capital, but they must avoid reducing Seoul to mere stereotypes. Instead, they should focus on creating authentic experiences that resonate with both local citizens and global fans. For global youth, Seoul Syndrome illustrates the power of emotional consumption. Their attraction to Seoul is not only about K-pop or trendy cafés; it reflects a desire for community, identity, and belonging in an uncertain world. Recognizing this, educational institutions, cultural exchanges, and digital platforms could expand programs that allow deeper interaction beyond surface-level consumption. Ultimately, the key recommendation is to treat Seoul not as a fleeting trend but as a sustainable cultural hub. By protecting its unique urban rhythms and fostering inclusivity, Seoul can continue to inspire the world while ensuring that its citizens are not left behind in the global branding race.

Seoul’s transformation into a symbol of emotional consumption reminds us that cities are no longer defined only by skyscrapers, infrastructure, or GDP figures. They are also shaped by the collective imagination and emotional attachments of those who live in them and those who long for them from afar. The so-called “Seoul Syndrome” reveals how a city can transcend its geographic boundaries to become a global cultural metaphor—a stage where the aspirations, anxieties, and dreams of a generation are performed. Yet this transformation brings with it a paradox. When a city becomes a brand, it risks being consumed as quickly as the latest fashion trend. Seoul must guard against turning into a surface-level spectacle, attractive only for its Instagrammable moments. The true strength of the city lies deeper—in the quiet resilience of its neighborhoods, the interwoven traditions of its people, and the ever-evolving stories that refuse to be commodified. For global youth, Seoul stands as both a mirror and a beacon. It mirrors their desire for belonging in a fragmented world, and it serves as a beacon for what a dynamic, culturally hybrid city can look like. For Koreans, it is a reminder that their everyday lives—walking by the Han River, sipping coffee in a Hongdae café, or supporting a local artist—are part of something larger than themselves: a shared emotional economy that now spans continents. The future of Seoul will depend not only on policymakers or businesses, but also on how its citizens choose to narrate their city. Will it be remembered merely as the capital of K-pop and trendy lifestyles, or as a place where emotional consumption was transformed into meaningful global connection? In the end, “Seoul Syndrome” is not just about one city. It is a case study in how places become feelings, and how those feelings can shape the trajectory of global culture. If Seoul manages to preserve authenticity while embracing its global role, it may well become the prototype of the emotional city of the future.